There are bad days in sport, and then there is 29 June 1950 – the afternoon when England contrived to lose to a team of American semi-pros at the World Cup in Brazil, while the West Indies spun them to a historic defeat at Lord’s. For collectors, the programmes and scorecards from that day capture a unique double disaster: humiliation on the football pitch at Belo Horizonte and a changing of the guard in cricket at the home of the game.

On paper, England travelled to Brazil as the self-styled “kings of soccer”, entering the World Cup for the first time. The Brazilians feared them enough to see the English as their main rivals and were building the vast Maracanã in expectation of lifting the trophy themselves. Reality turned out very differently.

A shambles from the start

England’s preparation for the tournament was almost comically inadequate. The squad’s training amounted to a kickabout at Dulwich on a reserve pitch before departure. Then came a 31-hour flight to Brazil, with stops in Paris, Lisbon, Dakar and Recife before finally reaching Rio.

No one had checked the hotel properly. Its beachfront location might have been perfect for a holiday, but the food was poor and the set-up hardly ideal for rest and focused preparation. Selection was in the hands of Arthur Drewry, a Grimsby fishmonger and FA representative; Walter Winterbottom, nominally the manager, was left largely to organise travel and logistics rather than tactics or team shape.

To make matters stranger, the FA had also dispatched a separate touring party of First Division stars to Canada and the United States at almost the same time. That squad included Stanley Matthews – arguably England’s greatest player – who was therefore not in Brazil for the opening fixtures.

Programmes and tour brochures from those parallel trips tell their own story: a governing body that did not fully grasp the scale and seriousness of the World Cup, still treating international football as an extension of exhibition tours rather than the pinnacle of the sport.

Chile beaten, but warning signs missed

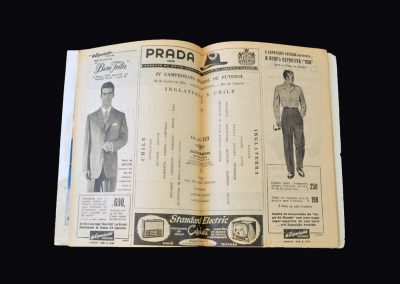

England’s campaign opened against Chile. The South Americans possessed one familiar name: George Robledo, Chilean-born but Barnsley-raised, soon to become a Newcastle United star and scorer of the winning goal in the 1952 FA Cup Final.

England won 2–0, but the performance lacked conviction. There was enough sloppiness for those close to the team to worry that something was off. Arrangements were made to fly Matthews down from the North American tour – another epic journey via Trinidad – in the hope that he could add much-needed guile. On the tournament schedule and in the Belo Horizonte match programme, however, his name never appears; Drewry chose to stick with the same XI for the next game.

That next game, against the United States, was seen as the “gimme” of the group. The FA touring team in Canada had beaten the USA in New York. The American World Cup squad were semi-professional at best: teachers, labourers, men with day jobs who played football on the side. England, even without Matthews, expected to stroll through.

-

BC All Stars v England 30.05.1950 & 03.06.1950

-

England v Chile 25.06.1950 (England's 1st ever World Cup Game)

-

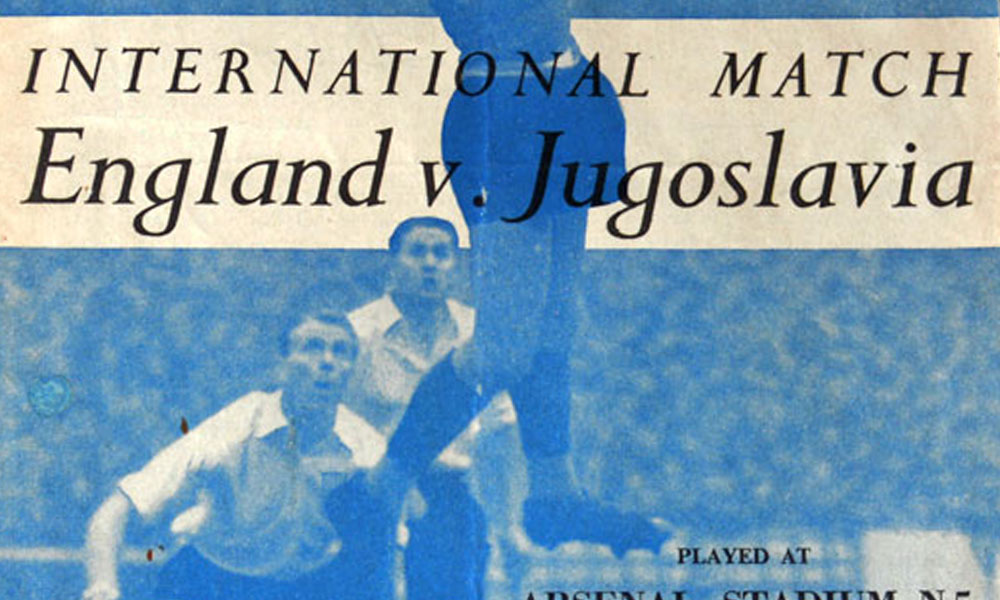

England v Yugoslavia 22.11.1950

-

England v Spain 02.07.1950

Meanwhile at Lord’s: Ramadhin and Valentine make history

Back home, attention was focused less on events in Brazil and more on the West Indies cricket tour. The visitors had never won a Test match in England before 1950. They lost the first Test, but arrived at Lord’s for the second determined to change history.

What followed became immortalised in Lord Beginner’s calypso “Cricket, Lovely Cricket”. The “two little pals of mine”, Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine, spun England to defeat in four days. Ramadhin took 11 wickets in the match, Valentine seven, as West Indies won by 326 and 425 for 6 declared against England’s 151 and 274 all out.

Thousands of Caribbean migrants from the Windrush generation, now settled in areas such as Notting Hill and Brixton, turned Lord’s into a sea of joyous celebration. For the staid old ground, it was an atmosphere rarely, if ever, seen before. The West Indies would go on to win the series 3–1, and their victory at Lord’s became a landmark in both cricket and post-war British social history.

Among England’s cricketers not selected for that series was Willie Watson, Sunderland right-half and top-order batsman for Yorkshire. Watson was in Brazil as understudy to Billy Wright, but never kicked a ball at the World Cup. Ironically, his absence from the West Indies Tests meant he was spared one sporting disaster, only to be connected with another.

For memorabilia collectors, a Lord’s scorecard from that second Test, placed alongside the Belo Horizonte programme, tells a remarkable parallel story: old certainties in both of England’s great summer sports being challenged and overturned.

Belo Horizonte: the “impossible” defeat

If the cricket represented a change in the balance of power, the football match against the USA was something else entirely: a shock so great that some English newspapers reportedly assumed the scoreline was a misprint. Surely it must have been 10–1, not 0–1?

On the day, England created enough chances to win comfortably. They hit the woodwork, missed sitters, saw penalty appeals waved away and ran into an inspired goalkeeping performance from Frank Borghi. Anyone who recalls the 1973 draw against Poland at Wembley can recognise the pattern: dominance in possession, but no way through.

Then came the moment that would define the match. A speculative American shot, seemingly manageable for goalkeeper Bert Williams, was diverted by a flying header from centre-forward Joe Gaetjens. The ball skewed to Williams’ left and into the net. 1–0 United States – and that is how it stayed.

At the final whistle, Gaetjens and Borghi were chaired from the field, with manager Bill “Chubby” Jeffrey carrying the match ball. For them, it was a sporting miracle. For England, it was humiliation.

The epilogue is darker still. Gaetjens, an educated Haitian who had been working in the USA, returned home in 1964. His brothers were considered rebels by the regime of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Shortly after his return, Gaetjens was arrested and “disappeared” by the authorities. His fate was never formally confirmed; only the memory of that goal lives on.

Spain, Maracanazo and muted headlines

Technically, England still had a chance to progress if they could beat Spain in their final group match. Instead, they lost 1–0 again and flew home, their first World Cup adventure ending in disappointment and introspection.

Brazil, who had feared the English so much, reached the final round-robin and needed only to avoid defeat against Uruguay at the Maracanã to secure the title. In front of an enormous home crowd, they lost 2–1. The “Maracanazo” triggered national trauma: reported suicides, threats against the goalkeeper, and a deep sense of shame. Brazilian football would rebuild and ultimately find redemption with the 1958 World Cup win in Sweden.

Back in England, newspaper sports pages that summer were dominated more by cricket than by football. Given the shock around both results, that distraction may have been a blessing. The USA defeat was so unthinkable that rumours persisted of a typesetting error. But the scoreline was real, and for many years it stood as the greatest upset in World Cup history.

Programmes, scorecards and the memory of a bad day

For a site like 10footballs, it is this kind of layered story that makes match programmes and related ephemera so fascinating.

A Belo Horizonte programme with England and the USA listed side by side is more than a curiosity; it is the paper witness to an era when the FA still believed reputation and talent alone would carry the day. A Lord’s scorecard from the second Test of 1950 shows Ramadhin and Valentine dismantling English batting, watched by jubilant West Indian supporters who were reshaping the culture of the game.

Add in tour literature from the FA’s simultaneous Canadian trip, Willie Watson’s dual-sport legacy, and the later images of the Maracanã in stunned silence, and you have a powerful set of artefacts that capture a moment when English sporting supremacy was questioned on two fronts at once.

On 29 June 1950, England had a very bad day at the World Cup – and an equally bruising one at Lord’s. Today, the paper relics of that afternoon allow us to revisit not just the scorelines, but the complacency, change and human stories wrapped up inside them.