The 1954 World Cup in Switzerland arrived in June, straight on the heels of a full English season, and England travelled with a curious mix of confidence, complacency and concern. In the background sat an attitude that still feels astonishing: the tournament was often treated by the domestic game as something close to an extended summer jaunt, with precious little thought given to recovery time, preparation, or the simple fact that the rest of Europe were training differently and thinking differently.

Qualification itself barely helped sharpen the mind. FIFA’s route for the Home Nations meant the top two in the Home International Championship went through, which usually made the process feel more like a formality than an exam. The sense of inevitability was comforting, but it was also dangerous. It allowed England to drift into Switzerland still clinging to old assumptions about stamina, spirit and “knowing our game”.

Getting there: Wales, Northern Ireland, and a glamorous warning shot

England’s qualification began with a 4–1 win over Wales in Cardiff on 10 October 1953, yet even that comfortable scoreline carried a whiff of warning. Wales had spells on top and were unlucky with an injury to full-back Alf Sherwood – in the era of no substitutes, he returned more as a passenger than a participant. England took their chances through Nat Lofthouse and Denis Wilshaw, while Gil Merrick’s best moments arrived at just the right time.

Ten days later came a match that, in programme-collecting terms, is a jewel because it feels both celebratory and prophetic: the FA’s 90th anniversary fixture against a “Rest of the World” XI. It finished 4–4, with a late Alf Ramsey penalty rescuing a draw, and Stanley Matthews recalled at 38. More important than the score was the style. A collection of European players, thrown together with minimal preparation, moved the ball with a fluency that made you wonder what a properly coached continental side might do to England.

On 11 November, England beat Northern Ireland 3–1 at Goodison Park to effectively seal qualification, but contemporary reaction was hardly rapturous. The feeling was that England were still winning without persuading anyone they were evolving.

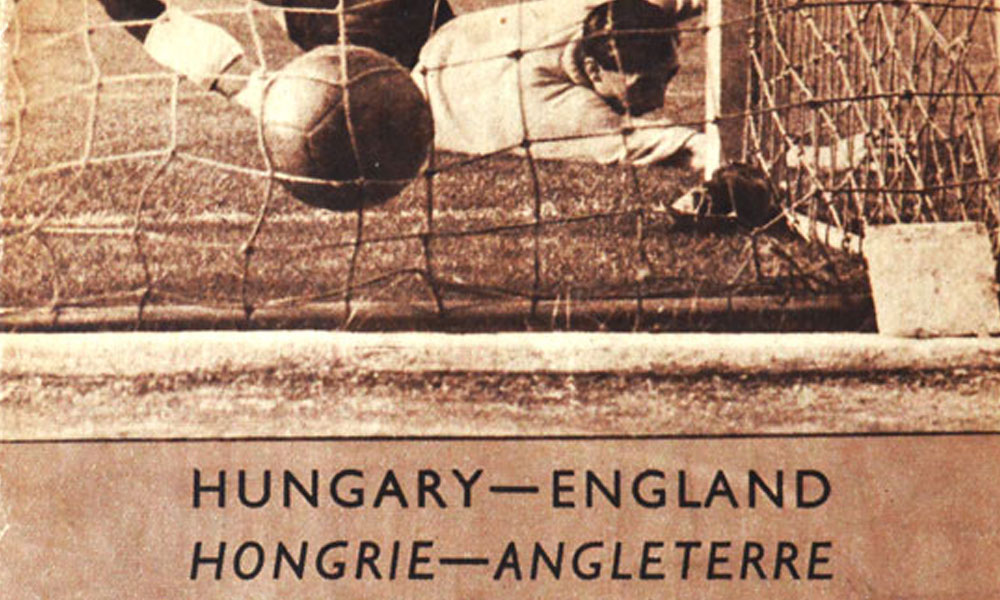

The match that changed the mood: Hungary at Wembley

Then, on 25 November 1953, Hungary arrived at Wembley and smashed the most stubborn myth in English football: that nobody could come here and outplay us. Hungary were Olympic champions, a unit that trained together, attacked together and understood space in a way England simply did not. The 6–3 scoreline is famous; the deeper truth is that England were made to look tactically naïve. Billy Wright’s famous slide, stranded by a Puskás feint, became a symbol of a system being left behind.

The response, predictably, was to talk about preparation and coaching. Walter Winterbottom’s situation was repeatedly highlighted: England selections were still tugged around by club football, selectors, and the relentless chase for league points. The programme notes from the period are full of earnest calls for training camps and longer spells together – all sensible, all difficult to deliver in that era.

Hampden, selection churn, and a spring of “trials”

By April 1954, England went to Hampden Park and beat Scotland 4–2. The win mattered for pride, and it also had a practical benefit in shaping the World Cup group allocation. It came after eight changes from the side humbled by Hungary, plus four debutants – including Roger Byrne, who would soon make the left-back slot his own before his tragic death at Munich in 1958.

The spring also became a carousel of representative “trial” matches and touring lists, with the World Cup “longlist” concept very much alive. On 10 February, the English League played the League of Ireland at Maine Road and won 9–1, a result that told England almost nothing about how to cope with elite tactical football.

-

Hungary v England 23.05.1954

-

England v Belgium 17.06.1954

-

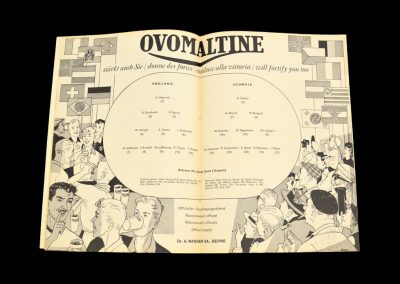

England v Switzerland 20.06.1954

-

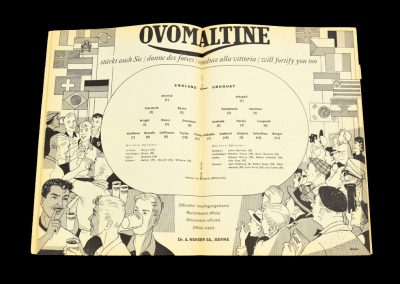

Uruguay v England 26.06.1954 | World Cup Quarter Final

The Eastern Europe warm-up: Yugoslavia… then catastrophe in Budapest

A two-match warm-up tour in May should have steadied nerves. Instead, it sharpened fears. England lost 1–0 to Yugoslavia in Belgrade, undone late by a deflected chance, and then came the heaviest defeat in England’s history: a 7–1 loss to Hungary in Budapest on 23 May 1954. England were relieved to escape without double figures. In collecting terms, those programmes sit in the same painful bracket as the Wembley 6–3: essential, because they mark the moment the old certainty truly died.

Switzerland: goals, chaos, and a quarter-final reality check

England arrived in Switzerland not quite knowing what to expect, except that Hungary looked like the tournament’s standard-setters. England’s own group stage began on 17 June in Basle against Belgium and promptly turned into one of the maddest matches in World Cup history: a 4–4 draw. England were the better side for long spells and led 3–1 early in the second half, with Matthews influential, yet casual defending dragged Belgium back into it. Lofthouse scored again in extra time, only for an own goal to make it 4–4. It was thrilling, wasteful, and oddly revealing: England could attack, but they could not control the temperature of a match.

Three days later, England beat Switzerland 2–0 in Berne, a steadier performance made more impressive by the absences: Matthews and Lofthouse were ruled out, and Billy Wright was moved to centre-half. England progressed to the quarter-finals without even meeting Italy, because the tournament’s seeding format kept certain sides apart in the group stage.

On 26 June came Uruguay. As holders from 1950, they were formidable, and England actually produced their best display of the finals. At 3–2 England were still properly in it, but a second major error by Gil Merrick pushed the score to 4–2 and ended the run. Matthews, now 39, was outstanding; the defence battled; but England were out.

Why this tournament belongs on 10footballs

On 10footballs, the charm is that football history is told through the programmes themselves – the ephemera that carries match detail, tone, and the mood of the time. The key pieces for this story are neatly anchored in the site’s “England 1953/54” section, which pulls together many of the season’s defining programmes, including the build-up matches, Bannister’s four-minute mile moment in the same sporting summer, and the pre-tournament tour fixtures. The World Cup ties also sit naturally alongside the dedicated “1954 FIFA World Cup Switzerland” grouping, which acts as a clean route for collectors who prefer tournament sets.

And if you want a brilliant side-thread that programme collectors love, the Duncan Edwards pages capture the era’s wider context, including the note about an uncapped 17-year-old being named in England’s initial World Cup 40 before the final squad was chosen – exactly the sort of “nearly” detail that makes programme-led storytelling feel alive.

In the end, England’s 1954 World Cup wasn’t a disaster, but it was a loud lesson. The pupils had surpassed the master, and England were being forced – slowly, stubbornly – to learn a new language of football.