“My dad always said you have to be mad to be a goalkeeper.”

For a lot of us, that line sounds like a joke about the kid who gets stuck in nets because no one else fancies it. But for older generations, it had a far more serious edge. It came from a time when goalkeepers had almost no protection, when charging the keeper was part of the game, and when diving bravely at a forward’s boots could genuinely be a life-threatening decision.

On 10footballs.com, we celebrate football history through programmes and memorabilia. Behind those neat line-ups and adverts, though, are stories of real risk – and nowhere is that clearer than in the treatment of goalkeepers in the early and mid-20th century.

The brutal reality for early keepers

Up until the 1930s, the laws of the game made life between the posts downright dangerous. Forwards were expected to challenge the goalkeeper aggressively. As long as the keeper did not have the ball completely under control, it was deemed fair game to go in with raised boots, shoulder charges and hacks at the ball – and if they caught the man as well, that was often just “unlucky”.

Today, a high boot near the goalkeeper usually brings an instant whistle and often a booking. Back then, it was simply part of the job. Two of the era’s finest keepers paid the ultimate price for that culture.

-

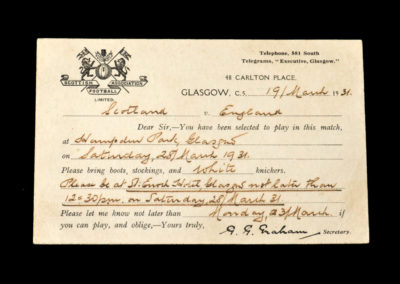

Scotland v England 28.03.1931 John Thomson Selection Card

-

Sunderland v Chelsea 01.02.2011 (75th Anniversary of the death of Jimmy Thorpe)

John Thomson – a nation’s number one lost

In September 1931, Celtic’s John Thomson – already Scotland’s established number one – lined up for an Old Firm derby against Rangers. During the match, he raced out for a loose ball at the same moment as a Rangers forward closed in. Both were committed, both went full-blooded into the challenge. Thomson took a catastrophic blow to the head.

He never recovered. The injuries were so severe that he died later that night. Contemporary reports and surviving footage make it clear the Rangers forward wasn’t acting maliciously; he was doing what forwards were encouraged to do, attacking the ball with everything he had. The tragedy lay in the fact that a goalkeeper’s bravery, under those laws, carried terrible risk.

Match programmes and selection cards from that period show Thomson as a fixture in the Celtic and Scotland line-ups. For collectors, those pieces are now poignant reminders of a career – and a life – cut brutally short.

Jimmy Thorpe – finishing the game, then never playing again

Just a few years later, in February 1936, Sunderland’s Jimmy Thorpe suffered a similar fate in a league game against Chelsea. A policeman on duty that day recalled seeing Thorpe gather the ball into his chest and drop into a kneeling position as two Chelsea players bore down on him. One kicked him on top of the head; more kicks followed as players hacked at ball and man in the resulting scramble.

Thorpe later said he believed he had been kicked once in the head and three times in the upper body. With no substitutes allowed, he stayed on, “evidently dazed and rubbing his head”, and finished the match. Within days he was dead.

At the inquest, his diabetes was bizarrely cited as the primary cause of death, despite the fact he had played 52 consecutive games without needing medical attention. Sunderland went on to win the league that season; his championship medal was presented, not to a jubilant keeper, but to his widow.

Again, the programmes from that title-winning season – with Thorpe’s name calmly printed at number one – now carry a deeper weight. They are pieces of paper that remember a man whose courage, in the context of the rules at the time, proved fatal.

Law changes – and a slow shift in attitude

Those high-profile tragedies helped drive changes to the Laws of the Game. Raising a boot to a goalkeeper in possession of the ball was outlawed, and referees were encouraged to clamp down on the worst excesses of charging the keeper.

But culture shifts slowly. The image of the goalkeeper as a tough, almost expendable figure persisted well into the 1950s, and some of the most infamous examples of keepers being battered came not in routine league matches, but on the biggest stage of all – the FA Cup Final.

Trautmann, Wood and Gregg – the Cup Final batterings

Three successive FA Cup Finals – 1956, 1957 and 1958 – all featured serious incidents involving the man in goal.

In 1956, Manchester City’s Bert Trautmann, a former German POW who had become an unlikely hero in English football, dived courageously at the feet of a forward late in the game. He took a heavy blow to the neck. Dazed, he played on for the remaining minutes, helping City see out the win. Only three days later did X-rays reveal that he had actually broken a bone in his neck.

The following year, Manchester United’s Ray Wood lasted only a few minutes of the final after a supposedly legal shoulder charge from an Aston Villa forward left him with a broken jaw. With no substitutes allowed, United initially had to reshuffle with an outfield player in goal. Incredibly, they later brought Wood back onto the pitch as a “nuisance” winger – a body in a shirt to make up the numbers, despite his concussion and broken face.

In 1958, United were back at Wembley, this time in the shadow of the Munich air disaster. Their goalkeeper Harry Gregg stayed on the pitch for the full final, but not without controversy. Bolton’s Nat Lofthouse famously bundled him, ball and all, over the line for the decisive goal with a heavy barge to the chest. The referee allowed it. Today it would almost certainly be whistled as a foul; in 1958, it was just “robust centre-forward play”.

Cup Final programmes from those years are among the most collected items on 10footballs.com. They chart the line-ups, the route to Wembley and the day’s occasion – but behind the neat typography lurk stories of broken bones, battered jaws and keepers expected to carry on regardless.

-

St Helens v Burscough 09.10.1948 (Trautmann in goal for St Helens)

-

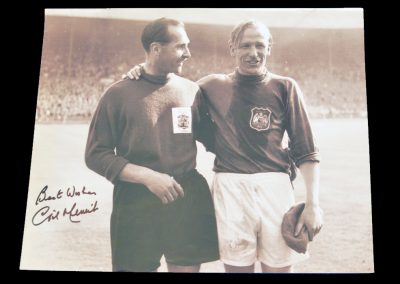

Trautmann Photo

-

Bert Trautmann Testimonial match 15.04.1964

-

Man Utd & City v All Stars 15.04.1964 - Bert Trautmann Testimonial

From “cowardice” to concussion protocols

In those mid-century years, concussion was barely a recognised concept in football. Going off with a head injury carried an air of shame, as if you were letting your team-mates down. Playing on, however dazed, was seen as the braver choice.

Contrast that with today, when goalkeepers are (in theory at least) protected by strict concussion protocols, more generous substitution rules and a refereeing culture that errs on the side of safety. Charging or kicking at a keeper holding the ball is a quick route to a booking or red card, not a pat on the back from your manager.

Fathers are far less likely now to tell their children to avoid goalkeeping because it is too dangerous. The “you have to be mad” line survives, but it is usually delivered with a smile rather than a wince.

Collecting the stories behind the gloves

For programme and memorabilia collectors, goalkeeper stories like these add a rich layer of meaning to otherwise ordinary items. A Celtic or Sunderland home programme from the early 1930s, a Cup Final issue featuring Trautmann, Wood or Gregg, a team sheet with a famous number one – these are entry points into tales of courage, risk and a game that has changed dramatically in how it treats its most exposed position.

On 10footballs.com, each programme is more than a list of names and fixtures; it is a snapshot of an era. In the case of goalkeepers, it is also a reminder of a time when standing between the posts really did demand a touch of madness – and sometimes, heartbreakingly, a very high price.